Identification of High Alert Medications (HAMs) differs from one institution to another. However, all organizations identify four specific HAM drug classes—insulins, anticoagulants, sedatives, and opioids—because they’re frequently linked to potentially harmful outcomes.

Insulins

Reports received by ISMP reveal most insulin errors stem from human error (concentration lapses, distractions, and forgetfulness) related to dosage measurement and hyperkalemia treatment.

Most of these errors stemmed from knowledge deficits—for instance, related to differences between insulin syringes and other parenteral syringes and the perceived urgency of treating hyperkalemia.

Examples:

Treatment for hyperkalemic patients with renal failure may involve dextrose 50% injection (D50) and insulin to help shift potassium from the extracellular space to the intracellular space. This helps stabilize cardiac-cell membranes to allow time for other definitive treatments.

In one error reported to ISMP, the physician prescribed 50 mL of D50 along with 4 units of regular insulin I.V. (U-100) for a patient with severe hyperkalemia and renal failure. The nurse mistakenly drew 4 mL (400 units) into a 10-mL syringe and administered it I.V. The patient suffered severe hypoglycemia.

Other reports involving hyperkalemia treatment indicate D50 wasn’t given when the patient received insulin and became profoundly hypoglycemic.

Additional confusion can occur with U-500 insulin because it’s given in a tuberculin syringe, not an insulin syringe. A patient who receives 150 units of U-500 twice daily should be taught to withdraw 0.3 mL insulin in a tuberculin syringe.

Additional confusion can occur with U-500 insulin because it’s given in a tuberculin syringe, not an insulin syringe. A patient who receives 150 units of U-500 twice daily should be taught to withdraw 0.3 mL insulin in a tuberculin syringe.

Many patients and nurses mistakenly believe the patient’s receiving 30 units of insulin, not 150 units.

Some insulin errors result from storing multiple concentrations and drug strengths next to one another, similar packaging of some drugs, and design flaws of certain insulin pens.

With some pens, the user can easily misread the digital display of the dose when holding the pen upside-down. For example, a dose of 12 units might look like 21 units.

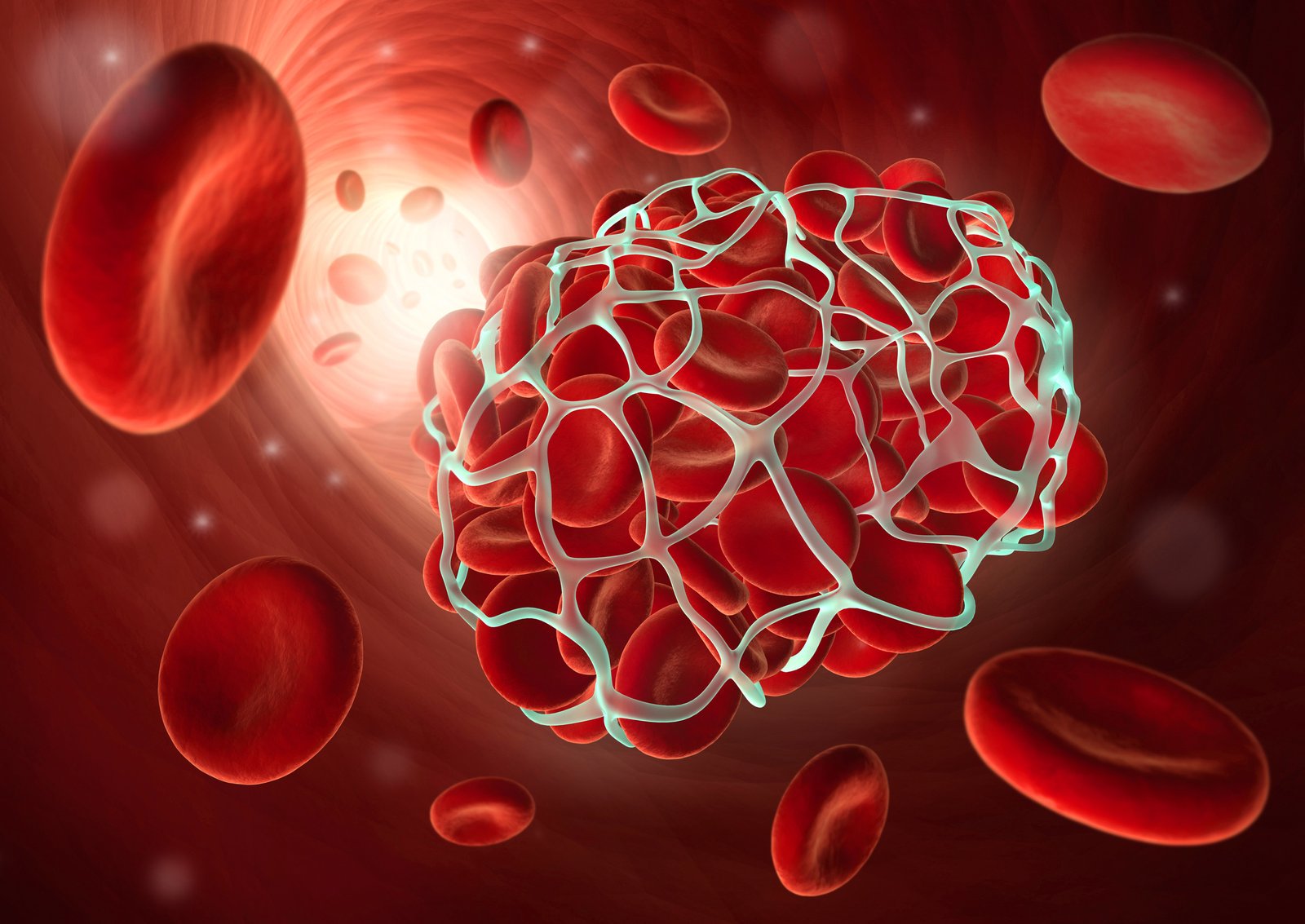

Anticoagulants

The most common anticoagulant errors are administration mistakes, including incorrect dosage calculation and infusion rates.

From 2010 – 2012, QuarterWatch (published by ISMP) noted an increased incidence of severe and fatal bleeding events in patients with a median age of 80. The FDA has received 7,387 reports of serious events associated with dabigatran, including 1,158 deaths.

In 2014, the agency released new information revealing that although dabigatran is less likely than warfarin to cause intracranial hemorrhage, it’s more likely to cause GI bleeding.

In the United States, many patients have switched from warfarin to dabigatran. However, no widely available laboratory test exists in this country to monitor dabigatran blood levels.

In Europe and Canada, the hemoclot thrombin inhibitor kit assay determines thrombin clotting time, which correlates to plasma dabigatran levels. Using this test would help clinicians identify patients at higher risk of bleeding.

Another disadvantage of the newer oral anticoagulants is lack of a reversal agent if catastrophic bleeding occurs.

Sedatives

Sedatives, such as chloral hydrate and benzodiazepines, commonly are given for procedural sedation and during hospitalization.

Inappropriate use can lead to oversedation, lethargy, hypotension, and delirium. Also, sedatives may increase the risk of falling. Sometimes, sedatives and opioids are administered together, with a synergistic effect that leads to central nervous system depression.

In addition, sedatives may lead to harm if clinicians aren’t familiar with the specific medication. For instance, they may titrate the dosage without knowing the upper dose limits, or they may be unaware of the drug’s onset of action. Harm also may occur if the patient experiences respiratory depression or respiratory arrest in a facility without appropriate safety measures.

The most common problem medications linked to an increased fall risk were sedatives, opioids, antihypertensives, anti-anxiety drugs, and antipsychotics.

Opioids

Even when prescribed in appropriate dosages, opioids can cause harm. In 2013, the Society for Critical Care Medicine released new guidelines for the treatment of pain, agitation, and delirium.

An August 2012 sentinel evert alert reported that 47% of opioid-related adverse events in hospitals from 2004 to 2011 resulted from incorrect dosages, 29% from improper patient monitoring, and 11% from other factors (including drug interactions, excessive dosing, and adverse drug reactions).

Some hospital patients use patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pumps to control pain. Based on reports submitted to the FDA, PCA pumps carry a threefold higher risk of injury or death than general device infusion pumps.

A review of the MAUDE database as of January 31, 2011, revealed 4,230 errors resulting in 826 injuries or deaths associated with PCA use, compared to 48,961 errors and 3,240 injuries or deaths associated with I.V. infusion pumps.

Despite the greater number of errors with PCA use, the percentage of injuries associated with errors is three times higher with PCA pumps than with I.V. pumps (19% vs. 6.7%). The majority of these PCA errors stemmed from erroneous pump programming or using the wrong medication in the device.

Source:

- Committee on Identifying and Preventing Medication Errors, Aspden, P, Wolcott J, et al. Preventing Medication Errors: Quality Chasm Series. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006.

- ISMP Medication Safety Alert. Misadministration of I.V. insulin associated with dose measurement and hyperkalemia treatment. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. August 2011

- Health Research & Educational Trust. Implementation guide to reducing harm from high-alert medications. 2012.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. How-to Guide: Prevent Harm from High-Alert Medications.Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2012.

- ISMP Medication Safety Alert. Your high-alert medication list—relatively useless without associated risk-reduction strategies. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. April 4, 2013.

- Joint Commission, The. Sentinel Event Alert 49. Safe use of opioids in hospitals. August 8, 2012.

- Keers RN, Williams SD, Cooke J, Ashcroft DM. Causes of medication administration errors in hospitals: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Drug Saf. 2013;36(11):1045-67.

- Mattox EA. Strategies for improving patient safety: linking task type to error type. Crit Care Nurse.2012;32(1):52-78.

- Ritter III HTM. Making Patient-Controlled Analgesia Safer for Patients. Pa Patient Saf Advis.2011;8(3):94-9.

- Tham E, Calmes HM, Poppy A, et al. Sustaining and spreading the reduction of adverse drug events in a multicenter collaborative. Pediatrics. 2011;128(2):e438-45.

- Thomas M. Evaluation of the personalized bar-code identification card to verify high-risk, high-alert medications. Comput Inform Nurs. 2013;31(9):412-21.

- Trbovich P, Prakash V, Stewart J, Trip K, Savage P. Interruptions during the delivery of high-risk Medications. J Nurs Adm. 2010;40(5):211-8.

- Westbrook JI, Woods A, Rob MI, Dunsmuir WR, Day RO. Association of interruptions with an increased risk and severity of medication administration errors. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(8):683-90.

- Baldwin K, Walsh V. Independent double-checks for high-alert medications: essential practice.Nursing. 2014;44(4):65-7.

- ISMP Medication Safety Alert. How FDA can help reduce dabigatran (PRADAXA) bleeding risks. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. February 13, 2014.

- ISMP Medication Safety Alert. Survey suggests possible downward trend in identifying key drugs/drug classes as high-alert medications. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. July 3, 2014.

Dr. Khalid Abulmajd

Healthcare Quality Consultant